The wilderness is—news flash—a wild, and scenic place. The fact that it occupies a romantic place in our brains outside the familiar is, in large part, the essence of its appeal. It also explains the sheer terror that many people associate with being out in that wilderness.

Hang around wilderness adventurers long enough, and you’re bound to overhear curious questioners playing what I call “The Game of What-ifs”:

What if you’re bitten by a rattlesnake?

What if you’re mauled by a bear?

What if a rabid pack of wild coyotes with anger issues launches a coordinated attack on you while you’re cozy in your tent peacefully dreaming of hamburgers and beer?

It’s a game that sheds light on the deeply held, and often deeply irrational fears that many of us conjure up immediately alongside (if not before) images of untouched mountains, rivers, and forests. The sad part is that so many of those fears stand in the way of people experiencing the beauty of the wilderness for themselves, and the freedom and self-sufficiency that comes with it.

The truth is that much of what we fear is a product of our imaginations running wild, of salacious headlines, or anecdotal stories extrapolated to the commonplace. Said another way—the stuff that poses a real risk in the wilderness is most often far less exciting than the stuff of your nightmares.

According to the CDC, there are somewhere between 7,000 and 8,000 venomous snake bites in the US each year. That’s 0.002% of the population for those who really like keeping score. The number of deaths from those bites each year? 5.

Bears? Since 1784, and including those inflicted by black, brown, and polar bears, there have been just over 180 fatal attacks in the US. A number roughly double that of the lives lost to bee, hornet, and wasp stings…every year.

Those fearsome, scheming coyotes? In the combined history of the US and Canada, there have been exactly…wait for it…2 recorded deaths.

None of this is an argument against being vigilant when it comes to wildlife encounters, quite the opposite. But it helps to put things in their proper perspective, to prepare for the most likely scenarios, and to stop spending precious energy worrying about the extraordinarily unlikely ones.

What exactly are you more likely to find out there? The bumps and bruises that are insufficiently sexy to make headlines on social media—a sprained ankle, a broken arm, a friend struggling to manage their diabetes or asthma, altitude sickness, blisters, gastrointestinal illness, soft tissue wounds, and many other common non-life-threatening injuries. Injuries and illnesses that still require competent care to prevent little problems from becoming big ones.

OK, so you’re willing to set aside your fears of lions, tigers, and bears to see what the wilderness has to offer. Great! There’s just one issue: you’ve now replaced those irrational fears with the rational ones. Maybe visions of hauling 70 pounds of emergency gear that would be the envy of any urban paramedic to deal with these possible maladies are now dancing through your head. Maybe those visions are cutting a little too close to your lasting memory, as a Boy or Girl Scout, perhaps, of marching off on a misguided (and painful) comedy-of-errors type mission into the wilderness.

But there’s a common thread among many of these memories that helps explain their misery: being prepared for all the hypotheticals that might spill forth from playing “The Game of What-ifs” is not a simple matter of carrying things. Preparedness is not a piece (or pieces) of gear. It’s not something you can weigh, or hold in your hand.

I’m a fan of the saying that the most important piece of gear you have isn’t one that you carry at all: your brain. Skills are weightless. Not only the practical skills of how to deal with common problems far away from definitive medical care, but the skill of calm that can be poured like a salve onto any situation that requires it. (Hint: pretty much every situation does.)

And if any of that sounds like fun, practical stuff to learn, then you might find yourself in the same boat that Ace and I did this past month: taking part in a Wilderness First Responder course offered via the Flagstaff Field Institute.

A program of the National Outdoor Leadership School (NOLS), Wilderness First Responder (WFR)—affectionately known as “Woofer”, for short—is the industry standard certification for anyone who makes their living in the wilderness. Think: professional guides, search and rescue workers, and even residentially challenged long-distance hikers (not that I know any of those).

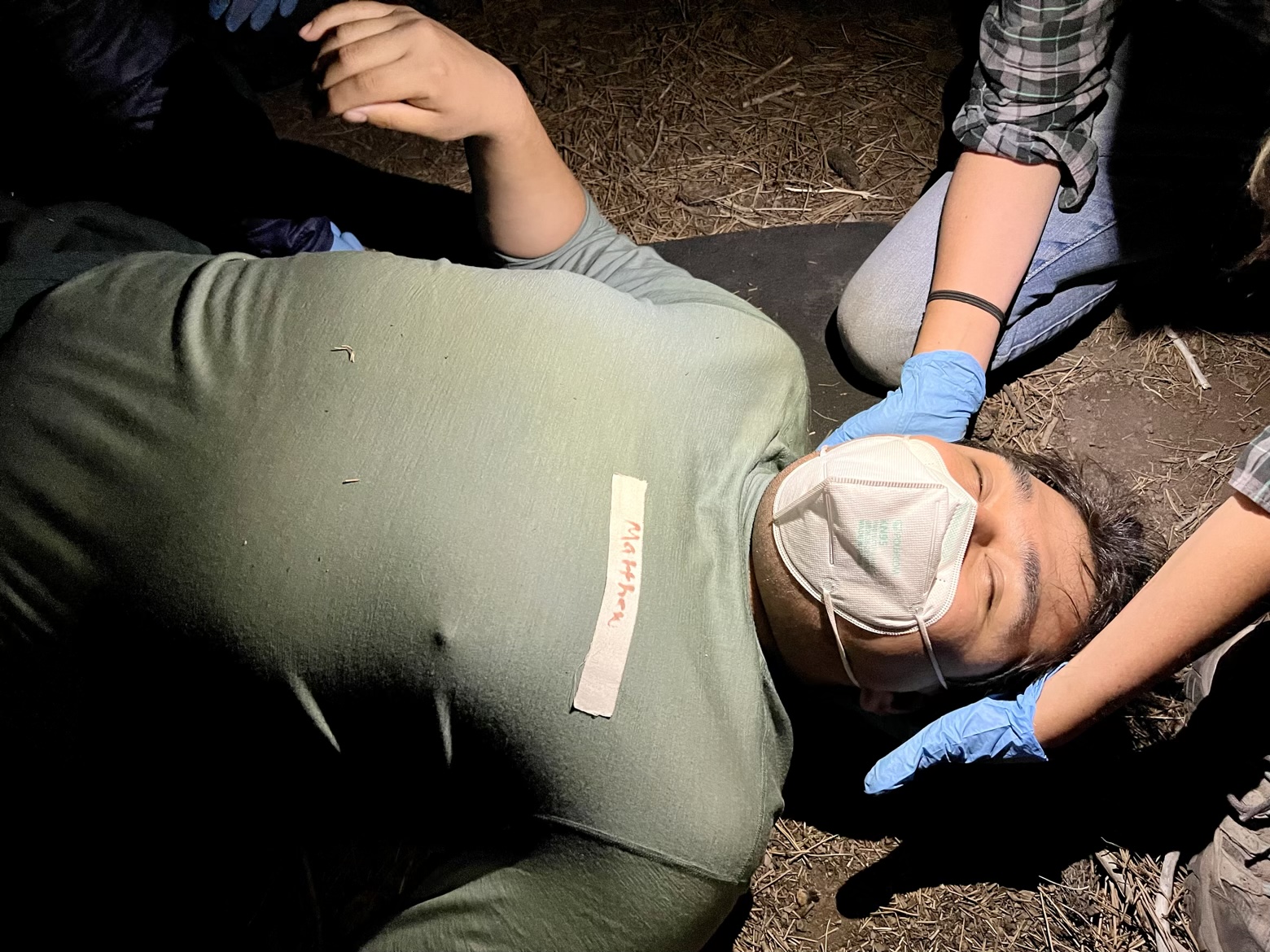

Classically taught as an intensive, 10-day in-person course mixing classroom work with dozens of mock rescue “scenarios”, the pandemic wrought changes even here. Recognizing the need to minimize in-person contact time while still preserving the critical in-person practice that the course seeks to hammer into your DNA, NOLS began offering a “hybrid” version of the course—spinning off the classroom component into 3 weeks of online coursework, immediately followed by 5 days of in-person practical work.

Culminating in both written and practical examinations, plus a nighttime rescue scenario that can only be described as an exercise in adrenaline management, this new “hybrid” version of the WFR curriculum maintains all the comprehensive, exhaustive training of the traditional version, all while making it more accessible to more people. You know, the people who might be interested, but not so much that they like the idea of burning 2 weeks of their precious vacation time just for the pleasure of immersing themselves in all things first aid.

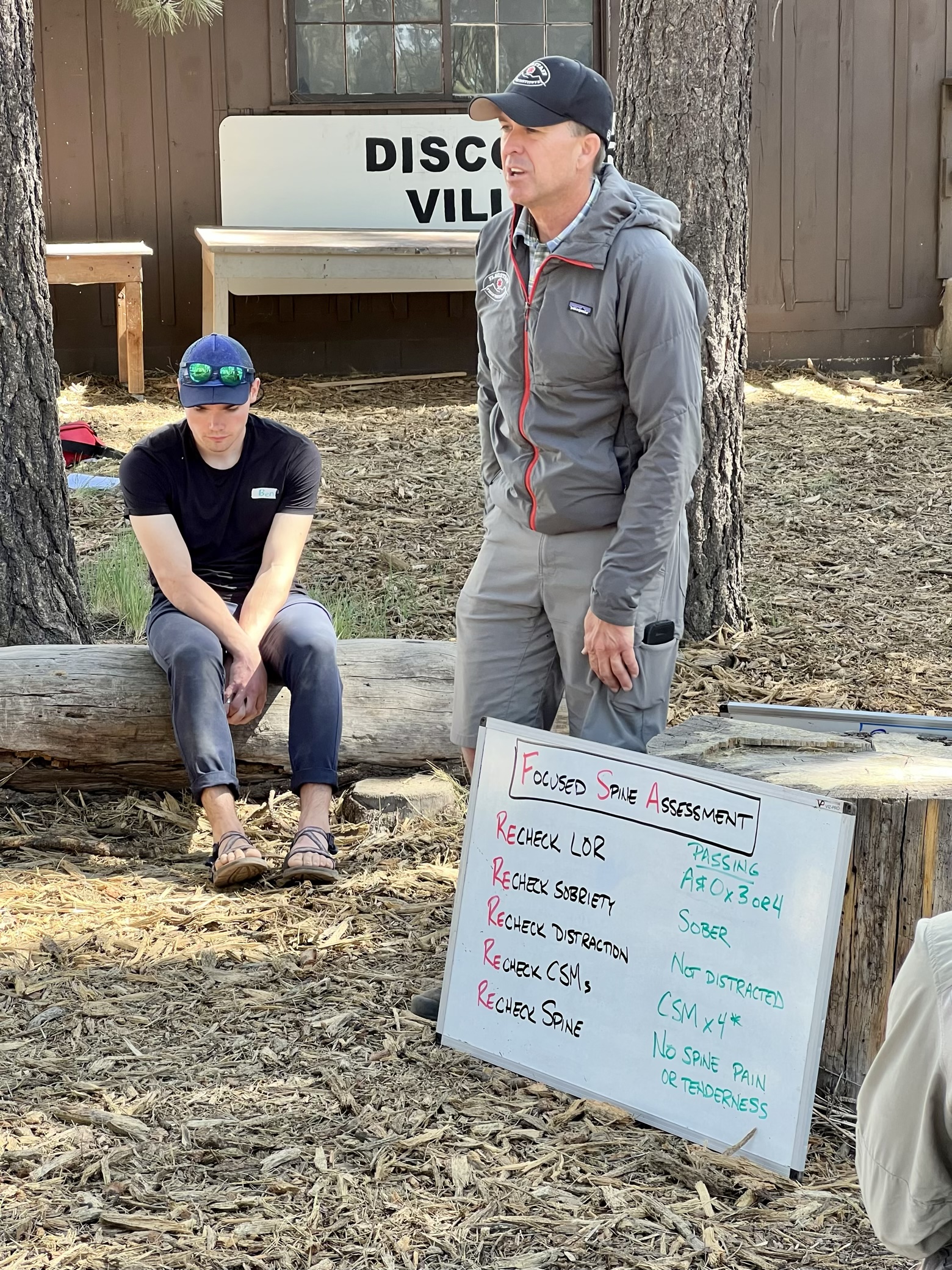

And so, after 3 weeks of online work that had us quizzing each other like college students, Ace and I landed among the pines of Flagstaff, AZ, alongside 25 fellow students from all manner of different backgrounds, ready to absorb all that we could from our instructors, Pete Walka and Brenna Meagher.

Deeply knowledgeable and organized, Pete and Brenna somehow managed to walk the tightrope of keeping the trains running on time, politely answering our questions and gently steering us away from the ditch that is “The Game of What-ifs”, all while keeping it light and fun. A course is only as good as its instruction, and these two exceeded any expectation we could have had.

Just how comprehensive was it? Here’s just a taste of the topics we delved into:

Traumatic Injuries

Shock

Chest Injuries

Brain and Spinal Cord Injuries

Athletic Injuries

Fractures and Dislocations

Soft Tissue Injuries

Burns

Environmental Injuries

Cold Injuries

Heat Illness

Altitude Illness

Poisons, Stings, and Bites

Lightning

Drowning and Cold-Water Immersion

Medical Emergencies

Allergies and Anaphylaxis

Respiratory and Cardiac Emergencies

Abdominal Pain

Diabetes

Seizures, Stroke, and Altered Mental Status

Urinary and Reproductive Medical Concerns

Mental Health

Expedition Medicine

Hydration

Hygiene and Water Disinfection

Dental Emergencies

Leadership, Teamwork, and Communication

Judgment and Decision-Making

Stress and the Responder

Medical Legal Concepts

Dizzyingly impressive as that list may be, we did not time warp and magically complete medical school in record time. Very, very far from it. What we did learn is that far from definitive medical care, and in lieu of being medical professionals ourselves, much of what WFR offers is the skill to judge what constitutes a true emergency in the backcountry. Understanding the difference between situations that require evacuation and those that can be safely and effectively managed in the field, all without carrying that 70 pound pack of gear I mentioned earlier.

Without a kitchen sink of medical supplies, the real skills being honed—aside from those that enable you to separate an injury that is life-threatening from one that is not—are maintaining calm under pressure and improvisation. Which explains why so much of WFR training emphasizes both practice and realism, complete with strikingly realistic moulage (stage blood), and fellow students giving Oscar-worthy performances of confused, unresponsive, or even screaming patients.

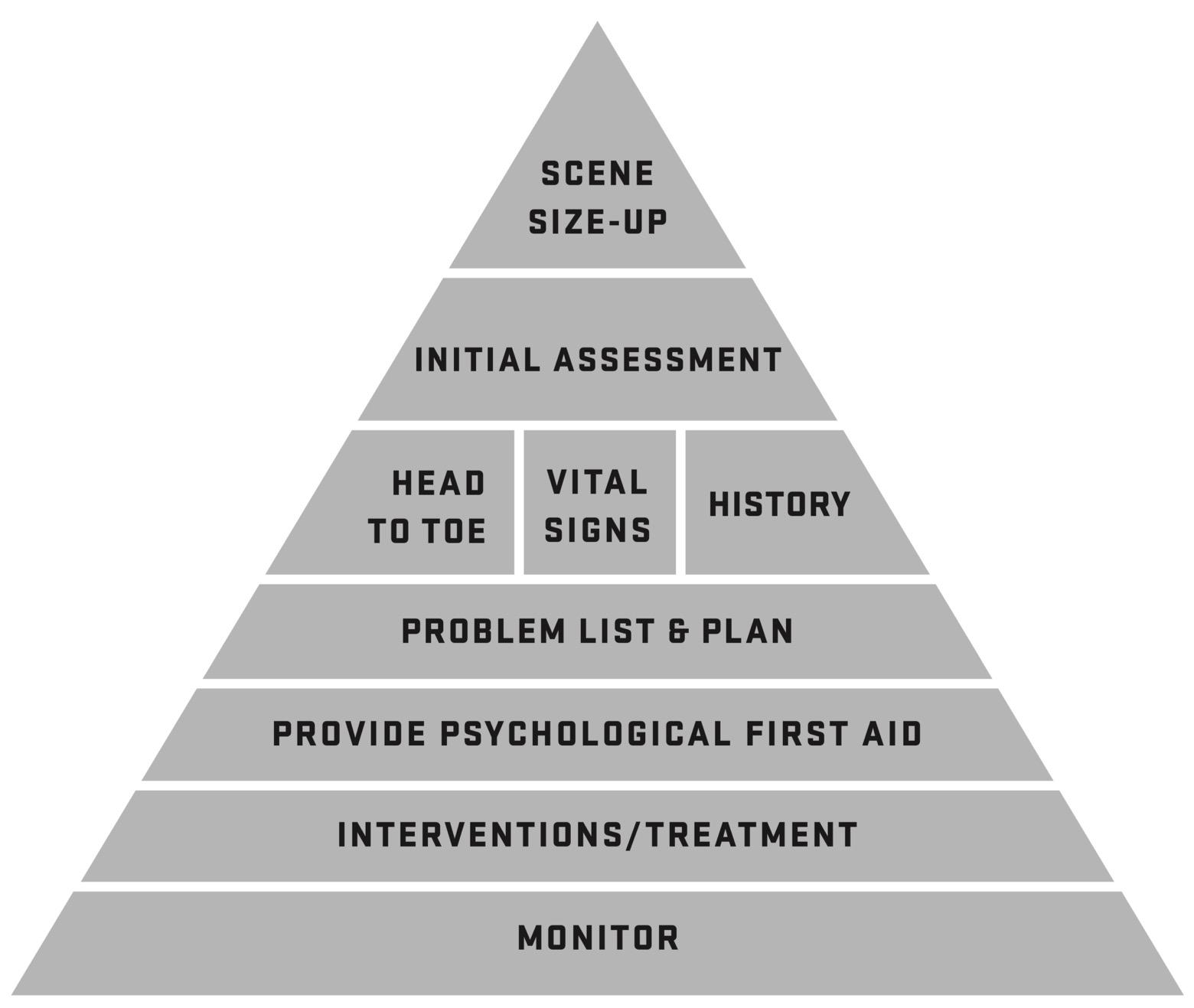

Of course, teaching people to learn calm under pressure isn’t like teaching them math. Sure, part of being calm follows naturally from learning and practicing the skills necessary to manage a specific medical problem. But learning a deeper notion of calm when it’s needed most requires a tool—one that you can rely on regardless of the specific situation—and that tool is the Patient Assessment System.

The cornerstone of WFR training, the Patient Assessment System—complete with its endless internal suite of acronyms and mnemonic devices—is the protocol that will always be there when you need it. Put simply, it’s a system for information collection that helps guide us to learn every detail that we can about the situation we’re dealing with and, ultimately, form a plan of how to deal with it.

Find a buddy who took a fall at the local climbing crag? Do a patient assessment. Your partner has a headache and seems confused while climbing Everest? Do a patient assessment. You come upon an unresponsive stranger in the middle of the trail? Do a patient assessment.

I now see this triangle in my sleep…

Why not always just err on the side of caution and call in the cavalry? Because even if: A) you have the ability to, and; B) you are successful, a wilderness rescue itself is not without risk, both to the rescuers and to the patient. In the air, weather conditions can endanger the pilots and crew members of evacuation helicopters. On the ground, arduous and lengthy travel over rough terrain to reach a patient can drastically increase the chance of injury to search and rescue workers.

Now picture those risks turning into reality for one unlucky rescuer, who in turn becomes a patient in the care of the other rescuers, all while responding to an emergency evacuation request in the wilderness. And when those rescuers finally arrive at the patient who had requested that evacuation, they find them with nothing more than a broken wrist, a small cut, and a set of perfectly functional legs and feet. Yeah, I’d be pretty pissed, too.

When I was an engineer, I often felt that the best definition of what it meant to be an engineer was to be a professional learner, to be forever a student. Situations constantly change and evolve, and learning is the adaptation required to evolve along with them.

Being prepared for challenges far away from hospitals and speeding ambulances requires that same dedication to learning. A Wilderness First Responder course might be an obvious fit for people who spend their lives as Ace and I do, but you don’t have to be an outdoor professional to gain the education it offers.

Among the painful lessons two years of a global pandemic have taught us is that people—not hospitals and not technology—are the true foundation of the healthcare systems that exist down the street from our homes, our schools, and our offices. Medical professionals, who themselves can become ill and be unable to provide us with the care we often take for granted, for life-threatening and non-life-threatening emergencies alike.

If it has taught us nothing else, it’s that anything we can do to help one another outside of those settings is something that benefits all of us.

I like to think that’s the real lesson that all 27 of us newly minted “Woofers” walked away with when Pete snapped the shutter of our graduating class on a beautiful sunny day at the Flagstaff Field Institute. We may have learned the skills to look out for ourselves more effectively on future journeys into the wilderness, but with those skills came an even greater, far more selfless form of knowledge: the empowerment to help someone else.